La máquina de futuro

La máquina de futuro

Bruno Varela

2024

Mexico 13’34’’, 16 mm and Super 8, colour, & BW 2024

March 8th, 2024 – 6 pm

The Machine of the Future (La máquina de futuro)

A film and an expanded cinema assemblage

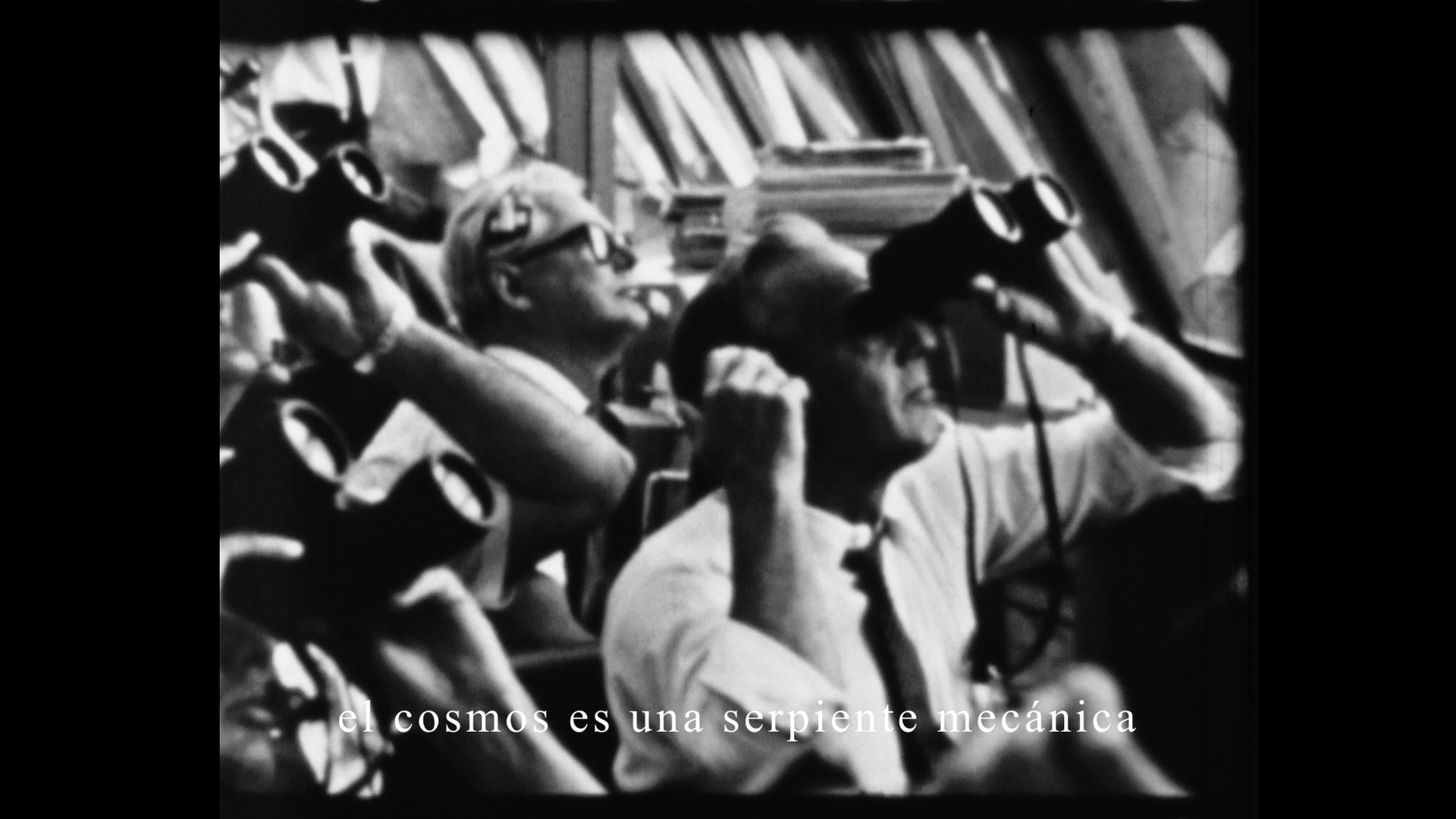

“Man on the Moon: A Film Record of the Apollo 11 Moon Conquest”: Regular 8 footage found in Los Sapos, Puebla, Mexico, in 2022.

“Inauguración Verástegui”: 16mm footage of launch of Verástegui automated tortilla machine (tortilladora) found in La Lagunilla, Mexico City, in 2016.

Speculative technology, prototypes for time machines. Repetition. Change, transformation of forms and possibilities for new ones.

Other lines of a possible future. Utopia, rituality, circularity.

A machine that involves the four elements and the core.

Anáhuac against the robots.

One tortilla is never the same as another, and yet they are always the same.

A machine operating against the system.

A machine of contradictions.

That always offers difference in repetition.

A rural dimension of technology, one that dreams of the original comal.

“If we are indeed doomed to the comically convergent task of dismantling the universe, and fabricating from its stuff an artifact called ‘The Universe,’ it is reasonable to suppose that such an artifact will resemble the vaults of an endless film archive built to house, in eternal cold storage, the infinite film.”

Hollis Frampton, “For a Metahistory of Film: Commonplace Notes and Hypotheses”

The Lemur people are older than Homo Sap, much older. They date back one hundred sixty million years, to the time when Madagascar split off from the mainland of Africa. They might be called psychic amphibians—that is, visible only for short periods when they assume a solid form to breathe, but some of them can remain in the invisible state for years at a time. Their way of thinking and feeling is basically different from ours, not oriented toward time and sequence and causality. They find these concepts repugnant and difficult to understand.

William S. Burroughs, “The Ghost Lemurs of Madagascar”

On Monday December 13, 1993, the following message was published in the Mexican newspaper La Jornada, signed by “Dr. Gerardo León Holkan”:

EUM

8 Ttekpatl-1968= 1981 /1 Akad-1987=2000

8 Tochtli-1994=2(XM)/13 Akad-t999=2012

Tiempo Cósmico

Mundial

C E.R. P.C. P. D.I. E.U. M.

Gómez Palacio, Dgo. Dic 13 de 1993.

Mechanizing Mexicanidad: Fundamental to approaching Bruno Varela’s film work is to understand that there is something of science fiction in every corn tortilla (centuries-old staple of the Mesoamerican diet). Indeed that mysterious element of commodity production is linked to the projective and epiphanic powers of found footage. As stated in the titles of Mano de metate (2018, in collaboration with Bruno’s daughter Eugenia Varela): “The tortilla is a representation of time, a comestible archive, without words. It has no definite shape; each tortilla is different, but it maintains resemblances with previous ones and those to come.” Every tortilla, like every piece of found footage, is a prototype.

In Varela’s early video Barrenador (2004), tortilla production occupies a central place in the geographically fragmented alimentary process that begins with the request for rain from Oaxaca’s Señor del Rayo (God of Lightning), and which is shown to be corrupted in the presidency of Vicente Fox by “green colonization” and genetically modified corn. And in Varela’s Tortillería Chinantla (2005), the mechanized rhythms of a tortilladora (corn tortilla-making machine) caught on Super 8 in Brooklyn, New York, become a “waltz” standing for both the obfuscation of human labor’s role in mass production and a vision of a future (or current) reverse colonization of the North. The references to the tortilla in Mano de metate are not isolated, since that film builds on the grindstone metate’s status as original Mesoamerican tortilla-making instrument, as well as some extended references to Chris Marker’s La Jetée (1962), to allow the tortilla’s contours to figure as symbols of time travel (a Mexicanization of Marker’s sequoia trunk in the Jardin des Plantes): “This is where I come from.” / “That is where it all begins.”

Varela’s new project, La máquina de futuro, premiered as an expanded cinema performance at the Muestra Mínima festival at the Chapingo Autonomous University in Texcoco, State of Mexico, in October 2023. 1 With the distance of two decades, we can now understand how seriously Varela meant Barrenador’s seemingly ludic juxtaposition of corn and a plastic astronaut figurine. In both the performance and the subsequent film called La máquina de futuro (2024), we are faced with two pieces of found footage, derived from two 1960s launches: a machine by Verástegui—foremost competitor of Veracruz’s Fausto Celorio, inventor of the modern tortilladora—presented under astral signs as “The Machine of the Future,” and the spectacular, universally significant colonial project of the Apollo 11 moon landing. 2 (A landing that ambiguously planted a U.S. flag as well as medals of fallen Soviet cosmonauts.) Twinned audio tracks of Apollo 11 and a YouTube video describing the Verástegui machine reinforce the film’s superimpositions. The “resemblances” mentioned in Mano de metate now encompass the lunar surface, with each tortilla bearing its own Sea of Tranquility.

In this work, the continuously spinning wheels of the Verástegui tortilladora (patented in 1959) rhyme with the rotations of the Eagle module above the lunar atmosphere, lending these pieces of found footage a sublime role—in their form and content—in Hollis Frampton’s “infinite film”: “The infinite film contains an infinity of endless passages wherein no frame resembles any other in the slightest degree, and a further infinity of passages wherein successive frames are as nearly identical as intelligence can make them.” A fine description of the máquina de futuro, that nevertheless—like Frampton’s fantasy of reassembling the universe in the shape of a film archive—cannot release us from the question of what sinister impulse might be lying behind it. Is it an instance of what philosopher Günther Anders called “Promethean shame”: an embarrassment that our universe is not our own product, and correlatively the false consolation that the Earth we are destroying is, because simulatable, therefore expendable?

In 1969, several months before Apollo 11, the person later responsible for publishing Frampton’s “For a Metahistory of Film” in Artforum—the scholar-critic Annette Michelson—wrote in the same journal as a response to Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968): “In a weightless medium, the body confronts the loss of those coordinates through which it normally functions.” The “reinvention of those coordinates” has the quality of dance movement. It is also the young who are “more openly disposed to that kind of formal transcription of the fundamental learning process which negates, in and through its form, the notion of equilibrium as a state of definition, of rest in finality.” The standing potential of found footage is, equivalently, to wrest the body from its familiar temporal coordinates. That loss of equilibrium, that dance involved in encountering footage and not knowing where to place it in time, exemplifies the temporal flexibility and and athleticism that Michelson labeled “modernism.” 3

The very same way of thinking about time is exercised in Varela’s main influences from science fiction and speculative prehistory. In Philip K. Dick’s 1981 novel Valis, the principle inspiration behind Varela’s feature El Prototipo (2022), a science fiction film generated by the transtemporal satellite signals of Christian Gnostics changes with each screening. And in another influence on Varela, Dick’s earlier 1964 novel Martian Time-Slip, “anomalous children” on Mars are “out of phase in time”: “precisely as we would be if we faced a speeded-up television program”—but also making possible the child Manfred’s “precognitive” visions (or prophecies).

William S. Burroughs’s cut-up and fold-in writing methods—conceived as a form of time-travel—have long constituted a spectral presence in found-footage experimental filmmaking, and Varela’s in particular: “When the reader reads page ten he is flashing forwards in time to page one hundred and back in time to page one,” the author says in “The Future of the Novel.” 4 Burroughs’s speculative prehistory of the Lemur people (inhabitants of the lost continent Lemuria) foregrounds their temporal flexibility. Such prehistories, like those surrounding the ancient city of Tiahuanaco in Bolivia, and emanating from a television program, form the backdrop of Varela’s film Parque Colosio (2013). An entire history has passed through the sieve of our received concepts.

“Anáhuac against the robots” (Anáhuac contra los robots): this phrase in Varela’s writing provides the title of the diptych consisting of La máquina de futuro and another tortilla-related short film, La ranura en el tiempo (2024), in collaboration with dancer Rosario Ordoñez Fuentes, partly filmed in 16mm in the ancient Zapotec city of Dainzú, Oaxaca, and sampled in the Chapingo performance. Thus, that ancient Zapotec city and the surface of the moon act as stages for a future confrontation between the Valley of Mexico (understood by its Nahuatl name, “Anáhuac”) and mechanical robots. And in consequence, nothing less than a vision of Neo-Mexicanist Millenarianism and its ambiguities (Is it a mechanized futurism or a militating against that?) emerges from Varela’s counterintuitively balletic transformation of Jean-Marie Straub’s last film, France Against Robots (2020), released to the world at the start of a pandemic and adapted from the French author Georges Bernanos. (“Regimes formerly opposed by ideology are now directly united by technology,” says Christophe Clavert in Straub’s France Against Robots, following Bernanos.)

These millenarian visions (beliefs in a radical transformation to come) were increasingly common in the late twentieth century, and in Mexico they often took on a neo-Mexicanist character. Thus, the diptych Anáhuac contra los robots would seem bound up with the late-century crescending of such omens as “the alignment of the planets that occurred in March 1982 up until the passing of Halley’s Comet in August 1986, the approach of the asteroid Icarus in 1988 or the lunar eclipse of 1993,” building up to that milestone year of Mexican history, 1994. 5 This was the year of the Zapatista uprising in Chiapas, of the assassination of PRI presidential candidate Colosio in Tijuana, and of Bruno Varela’s move to Oaxaca (following the call of Zapatismo to southern Mexico).

“[Max] Weber had already pointed out that subversive side of prophets and brujos, who move outside the priesthood or institution.” 6 The mechanical tortilladora, understood now as a machine for generating prophecies, by removing the subjectivity of the human hand (just like André Bazin’s vision of photography and cinema) is thus the radical negation of priestly institutions. And the idea of a machine for generating prophecies recalls (in La máquina de futuro, Varela’s quotation of) the series of mysterious mechanical-seeming prophetic messages published in the progressive Mexican newspaper La Jornada in 1993 and 1994, and later interpreted in Octavio Gordillo Guillén’s book Mensajes cifrados (Mexico City: Hoja Casa Editorial, 1997). Every approach to politics is ultimately a search for patterns, rendered in this case as a search for codes.

The ambition of a prophetic vision is to leave no significant event untouched. It is as though neither a liberating politics nor a cynical, genocidal politics could escape the presence of Ometéotl, Aztec god of creation. He is omnipresent, like a vision announced in El Prototipo of film as the skin that covers everything. He is self-generating, like the wheeling mechanisms of the tortilladora (feeding our continual nutritional cycles) and the phases of the moon. Ometéotl’s creative powers cannot be traced to a past event but are rather immanent in all things. 7

Every tortilla is a potential film.

Text by Bruno Varela and Byron Davies

1 In the performance, Varela was accompanied by Marcela Cuevas Ríos. The edition of Muestra Mínima at Chapingo was organized by Dahlia Sosa and Ricardo Benítez Garrido, and focused on agricultural themes, reflecting Chapingo’s character and historical significance.

2 By eliminating the definite article and exclamation mark in the sign visible in the Verástegui footage (La máquina del futuro!), Varela’s title both cracks open and cools the original’s marketing-enforced confidence.

3 See Daniel Morgan, “Modernism Is Not for Children: Annette Michelson, Film Theory, and the Avant-Garde,” Critical Inquiry 50, no. 1 (autumn 2023). A slightly different kind of temporal athleticism characterizes the main precedent for using footage of Apollo 11 in Mexican experimental filmmaking: Alfredo Gurrola’s La segunda primera matriz (1972), where the moon landing figures as a technologized return to film’s titular womb.

4 William S. Burroughs, “The Future of the Novel,” in Word Virus, ed. James Grauerholz and Ira Silverberg (New York: Grove Press, 1998), 96.

5 Francisco de la Peña, “Profecías de la mexicanidad: entre el milenarismo nacionalista y la new age,” Cuicuilco 19, no. 55 (2012), 127-143.

6 Astrid Maribel Pinto Durán and Martín de la Cruz López Moya, “Extraterrestres en el imaginario del New Age: redes de espiritualidad y utopía desde San Cristóbal de Las Casas, Chiapas,” LiminaR 9, no. 2 (2011), 63-82.

7 See Miguel León-Portilla, La filosofía náhuatl estudiada en sus fuentes, 11th ed. (Mexico City: UNAM Instituto de Investigaciones Históricas), 211-218.